Megastore for Thai Monks Brings One-Stop Retail to Buddhism

BANGKOK—On the western outskirts of town here, Hang Sangkapan sells everything the well-turned out Buddhist acolyte could need.

At the store, which translates as “Monk Supply,” aisles are stocked with candles, Buddha statuettes (both seated and standing) as well as altar tables, CDs, books and innumerable odds and ends for monks—be they novice or abbot.

Thailand has 61.5 million Buddhists among its 65.9 million people, nearly all of them practicing in the Theravada tradition. Males are expected to take the robe at least once in their lives. With heads shaved, they spend a few weeks seeking offerings and learning the Buddha’s teaching, disciplines and meditation.

For most, it is back to jeans and consumerism afterward. But some return and spend much of their lives in monasteries. According to the National Buddhism Office, Thailand had nearly 300,000 monks and more than 60,000 novice monks at the end of 2012.

And all of them need stuff.

Sakol Sangmalee founded the Hang Sangkapan—a sort of monk megastore—six years ago after a frustrating day crawling through Bangkok’s traffic-clogged streets in search of supplies for 99 poor novice monks he was sponsoring.

That meant 99 sets of robes, bowls and sundries. Elbowing his way from one tiny traditional shop to another, he says he was unable to find the items, and the quantities he needed, in one place.

During his less-than-uplifting outing, Mr. Sakol found that his car had been towed. He spent the rest of the day at the police station, paying a fine and getting his towed vehicle released.

But in his travails, he found inspiration: a megastore stocked to the rafters with all the food he needed. Carrefour, Makro, Lotus and other big-box outlets have revolutionized shopping in this Southeast Asian country since the 1990s. Surely, he thought, he could somehow clone this concept—tailoring it for the specific needs of monks.

“Consumer behavior has changed a lot,” says Mr. Sakol, a 52-year-old who is married with two grown children. “People are not loyal to any traditional monk supply shop anymore,” he says. “They will go wherever there’s an air conditioner and expect to get whatever they need in one visit.”

With 50 million baht, or $1.6 million, in capital—half from savings and half from a bank loan—Mr. Sakol opened Hang Sangkapan in 2007. Situated on more than a quarter-million square feet of land, his modern emporium is the largest Buddhist supply shop in the country by far—a one-stop warehouse carrying all things material for the spiritually inclined.

Of course, there is a parking lot.

Currently, he is in the midst of his busiest holiday season, Khao Phansa, often called Buddhist Lent, which begins Tuesday.

Among the one million items for sale are numerous obligatory saffron robes, which range from 1,000 baht ($33) for synthetic threads for monks on a budget, to several thousand baht for those desirous of more sumptuous cotton robes.

At traditional monk supply shops, the mood is usually discreet, with products typically bearing no price tags. Hang Sangkapan puts a decidedly more Western spin on religious commerce. Customers are “members”—although no Costco-like fee is required—and get up to a 5% discount on purchases with their loyalty cards. The store advertises on the Internet and offers phone orders and deliveries.

On a recent day, an elderly woman in a wheelchair spent two hours looking for ordination supplies that she believed suited her grandson. There were also full-time monks dragging carts through the aisles, stocking up on what they need.

“It feels like real shopping,” said Kaesinee Bumpennorakit, 48, who was planning to invite monks to her house and purchased cushions, packaged alms and a set of altar tables for the occasion.

“Hang Sangkapan is built for us,” says Pra Somwang Gunkogkrued, a 62-year-old monk who spends an hour every Saturday stocking up for himself and his temple. “I can buy many items such as Dharma books, joss sticks, candles, robes and ordination supplies,” he says. “It’s convenient and comfortable.”

Other local Buddhist-supply shop owners aren’t so impressed. They say they serve Bangkok’s more urban clientele and sniff that Mr. Sakol draws most of his car-friendly business from neighboring provinces.

“Hang Sangkapan is not our competitor,” insists Apaporn Wanglachatorn, part of a three-generation family shop. “We have loyal customers who order our products all the time, especially for Khao Phansa,” she says.

An elderly male family member interrupted her: “Hang Sangkapan is nothing…they just do it for business,” he said.

Mr. Sakol, who declines to disclose his earnings or margins, brushes away such criticisms and believes there is plenty of business to go around. He says he expects to make 30% to 40% of his annual sales during this season.

A study published last year by Kasikorn Research Center, an arm of a local bank, pegged money circulating in the monk-supply business at about 10 billion baht.

As part of his business, Mr. Sakol offers services and event-planning for Buddhist rituals. Teams make sure that everyone and everything shows up in the right place and the right time. While he hardly has the corner on that business, he has the advantage of ordering the requisite goods from his own giant store.

Mr. Sakol says he helped organize a birthday celebration for a woman from an elite family. To mark her 72nd birthday—an auspicious year in Thai Buddhism—she dropped two million baht. The woman, whose name he declined to disclose, had requested 79 monks at her house, with 10 of them of senior rank. Among other things, she wanted each to have special silk fans and bags.

According to Mr. Sakol, the megastore bring sales volume but event organization brings the profit. His next goal is to franchise. He thinks the country could do with hundreds of shops and is looking for investors.

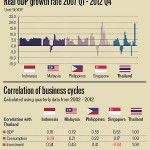

He is convinced that the Buddhism trade beats the lay business cycle. “Even when the economy slows down and political crisis [hits], people still want to make merit,” or do good deeds, he says. “They want to be happy and have good fortune.”

From: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324783204578619950520621128.html