Modern life takes toll on Thai monks

THE monks of this northern Thai village no longer perform one of the defining rituals of Buddhism: the early-morning walk through the community to collect food. Instead, the temple’s abbot dials a restaurant and has a takeaway delivered.

“Most of the time, I stay inside,” said the abbot, Phra Nipan Marawichayo, who is one of only two monks living in the once-thriving temple. “Values have changed with time.”

The gilded roofs of Buddhist temples are as much a part of Thailand’s landscape as rice paddies and palm trees. The temples were once the heart of village life, serving as meeting places, guesthouses and community centres. But many have become little more than ornaments of the past, marginalised by a shortage of monks and an increasingly secular society.

“Consumerism is now the Thai religion,” said Phra Paisan Visalo, one of the country’s most respected monks. “In the past, people went to temple on every holy day. Now they go to shopping malls.”

The meditative lifestyle of the monkhood offers little allure to the iPhone generation. The number of monks and novices relative to the population has fallen by more than half in the past three decades.

Although it is still relatively rare for temples to close, many districts are so short on monks that abbots in northern Thailand recruit across the border from impoverished Myanmar, where monasteries are overflowing with novices.

Many societies have witnessed a gradual shift from the sacred towards the profane as they have modernised. What is striking in Thailand is the pace of change brought on by the country’s rapid economic rise. In a relatively short time, the Buddhist monk has gone from being a moral authority, teacher and community leader fulfilling important spiritual and secular roles to someone whose job is often limited to presiding over ceremonies.

Phra Anil Sakya, the assistant secretary to the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, the country’s governing body of Buddhism, said that Thai Buddhism needed “new packaging” to match the country’s fast-paced lifestyle.

“People today love high-speed things,” he said. “We didn’t have instant noodles in the past, but now people love them. For the sake of presentation, we have to change the way we teach Buddhism and, like instant noodles, make it easy and digestible.”

Buddhist leaders should make Buddhism more relevant by emphasising the importance of meditation as a salve for stressful urban lifestyles, he added. The teaching of Buddhism, or dharma, does not need to be tethered to the temple. “You can get dharma in department stores, or even over the internet,” he said.

But Paisan is markedly more pessimistic about what is sometimes called “fast-food Buddhism”. He is encouraged by the embrace of meditation among many affluent Thais and the healthy sales of Buddhist books, but he sees basic incompatibilities between modern life and Buddhism.

His life is a portrait of traditional Buddhist asceticism. He lives in a remote part of central Thailand in a stilt house on a lake, connected to the shore by a rickety wooden bridge. He has no furniture, sleeps on the floor and is surrounded by books. Interviews are carried out at 6am, before he leads his fellow monks in prayer.

Monks are suffering a decline in “quantity and quality”, he said, partly because young people are drawn to the riches and fast-paced life of the cities. The monastic education of young boys, once widespread in rural areas, has been almost entirely replaced by the secular education provided by the state.

Government figures put the number of monks in the country at 290,000 last year, but Paisan said that Thailand had no more than 70,000 full-time monks.

Scandals surrounding monks have contributed to the decline. Social media has helped spread videos of monks partying in monasteries, imbibing alcohol, watching pornographic videos and cavorting with women and men, all forbidden activities. There have also been controversies involving allegations of embezzlement of donations at temples.

William Klausner, a law and anthropology professor who spent a year living in a village in north-eastern Thailand in the 1950s, described the declining influence of Buddhist monks as a “dramatic transformation”. Monks once played a crucial role in the community where he lived, helping settle disputes among neighbours and counselling troubled children, he wrote in Thai Culture In Transition.

Today, most villages in the area “have only two or three full-time monks in residence, and they are elderly and often sick”, he wrote.

In Baan Pa Chi, about an hour’s drive from the northern city of Chiang Mai, villagers describe a paradox. The monastery now has plenty of money, unlike decades ago, because former villagers who have moved to cities donate cash for new buildings, ornaments and statues, believing that they can “make merit” and improve their karmic status. But the monastery feels empty on most days.

“People used to leave their children here,” said Anand Buchanet, a 54-year-old construction worker who was a novice in the temple. “Now they just leave stray pets.”

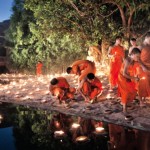

Novices once spent months in a monastery as part of what was considered an essential step for boys along the way to adulthood. Today, if they are ordained at all, boys typically spend a week in monk’s robes, giving rise to the term “factory monks” because they are churned out so quickly.

Nipan, the abbot, said his only real role today was to preside over rituals such as funerals, weddings and blessings of new homes. “People today have telephones,” he said wistfully. “If they have troubles, they call their friends.”

From: http://www.scotsman.com/news/international/modern-life-takes-toll-on-thai-monks-1-2704878